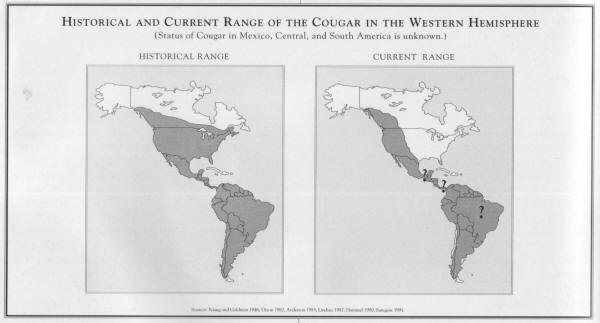

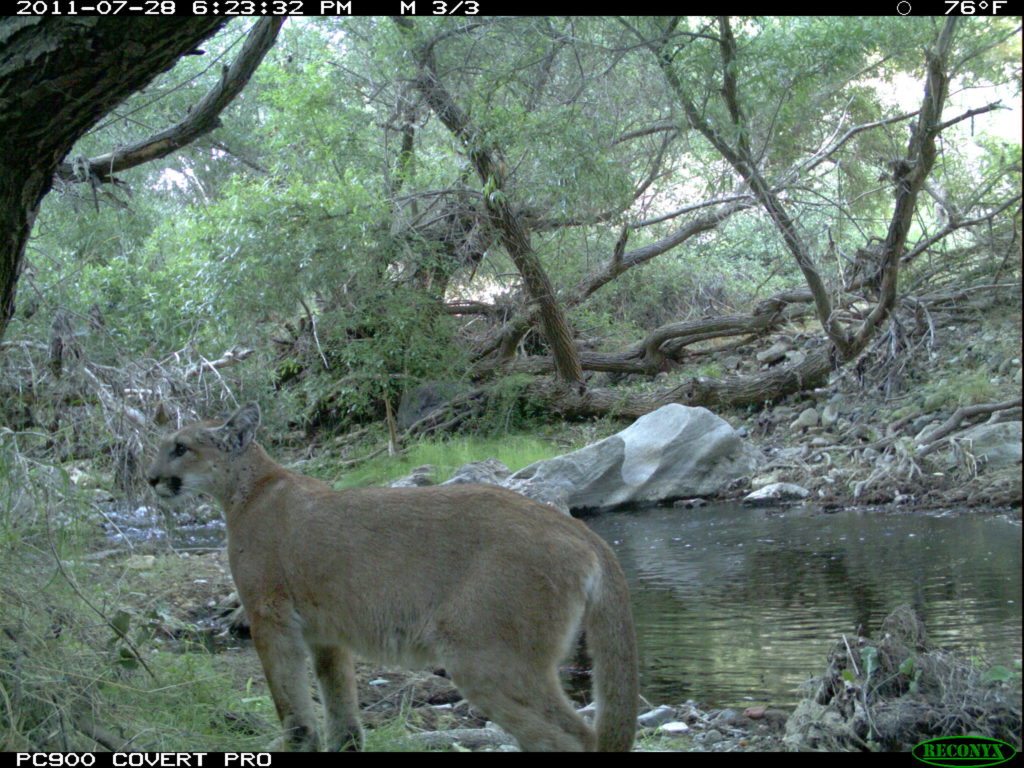

Mountain lions are known by many names, including cougar, puma, catamount, painter, panther, and many more. They are the most wide-ranging cat species in the world and are found as far north as Canada and as far south as Chile.

Solitary cats, mountain lions are highly adaptable to situations and environments, and this adaptability has enabled them to survive across much of their original range in the America's, despite severe habitat loss and active threats.

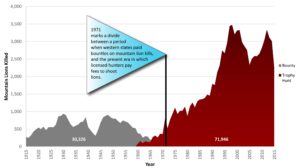

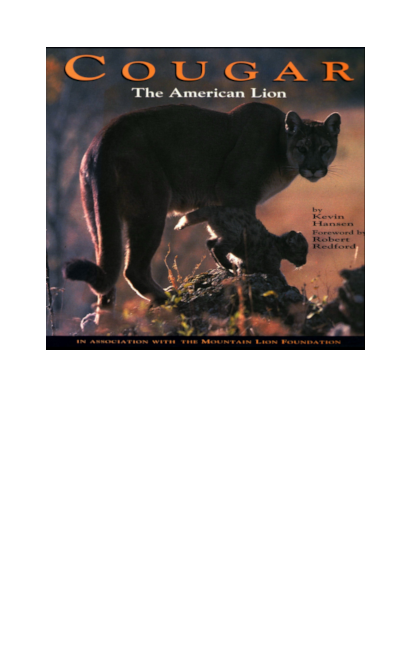

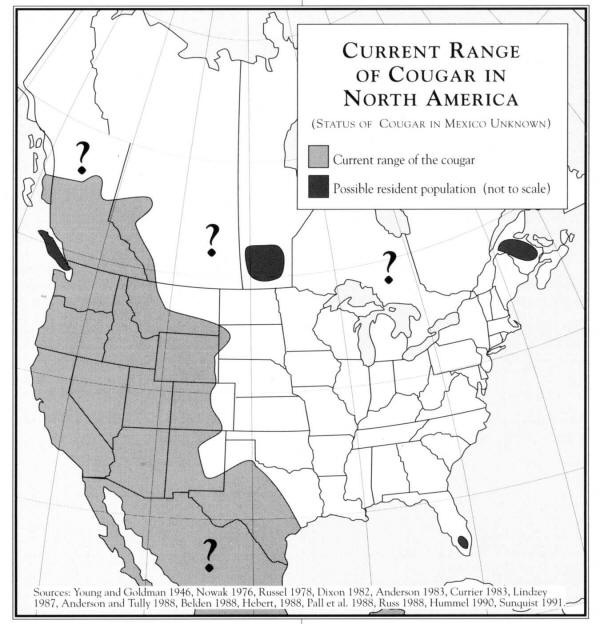

While their longitudinal range has remained, their latitudinal range has shrunk by more than half. Mountain lions used to be found throughout the United States, but due to bounty hunts in the early 1900s and threats such as persecution, trophy hunting, poaching, retaliation in response to livestock depredation, kitten orphaning, poisoning and habitat loss and fragmentation, mountain lions are now only found in 15 western states, and the genetically isolated Florida panther remains in the East. For more information about mountain lion life history, evolution and historical range, read Cougar: The American Lion below.

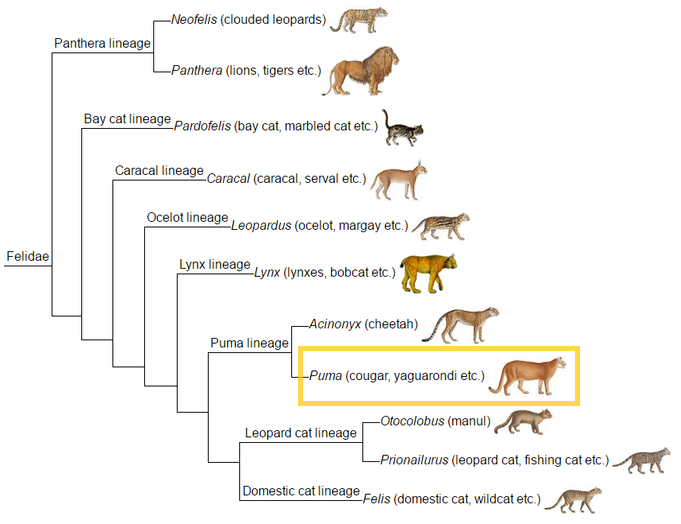

Mountain lions are members of the Puma lineage in the family Felidae. They have a long evolutionary history.

FUN FACT: Cheetahs are also a part of the Puma lineage. Mountain lions and cheetahs are not considered “big cats”, however, they are the largest of the “small cats”. Neither mountain lions nor cheetahs can roar, but both species can purr!

Mountain lions are obligate carnivores, meaning they only eat meat. As such, they have large canines and sharp, specialized carnassial teeth (molars) for shearing and tearing flesh. Mountain lions also have retractable claws, which they use to climb trees and capture prey. Their preferred prey are deer and elk and they have co-evolved with deer and elk as their primary prey.

Mountain lions have extraordinary vision. They have round or oval pupils, which allows them to open as wide as possible at night, but close almost completely in bright light, which protects light-sensitive cells.

Although there is little research on mountain lion hearing, it is known that domestic cats have very acute hearing and can detect prey using both sight and sound. They can hear frequencies in the ultrasonic range and are able to move their rounded ears together or independently to isolate sounds. It is also believed that an enlarged auditory bullae (the portion of the skull surrounding the middle ear) may enhance a cat’s sensitivity to certain sounds.

In mountain lions, the sense of smell is not thought to play a large role in acquiring food and is thought to be more important in social behavior, such as mating.

For more details about mountain lion senses, read Cougar: The American Lion – Chapter 4: An Almost Perfect Predator below.

Mountain lions are solitary cats. They are most active at dusk and dawn, known as crepuscular.

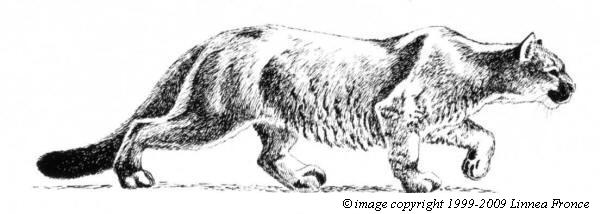

A relentless hunter. The search for prey is driven by the cat’s hunger and, in the case of a female, the need to feed growing kittens. The hungrier the cat, the greater the tendency to roam, with effort focused on areas where prey was previously found. The mountain lion navigates its home range in a zigzag course, skirting open areas and taking advantage of available cover. The cat’s keen senses are focused to pick up the slightest movement, odor, or sound.

For more details about mountain lion behavior, read Cougar: The American Lion – Chapter 4: An Almost Perfect Predator below.

When is enough… enough?

Mountain lions live a short 13 years in the wild — if they make it to old age. Today, few lions live a full natural lifespan.

It’s a difficult life, full of potentially lethal challenges: even when the lion avoids humans.

They are shot for recreation, for sport, and for trophies. They are shot when a rancher’s livestock is lost, and when pets disappear. They are shot when people are afraid.

Individual lions, and individual people, are diminished whenever we kill a lion unnecessarily. We lose not just a member of the species, but mother lions that might train their kittens to avoid people, large and well-established males that have proved themselves able to survive entirely in the wild, and lions that feel, think, experience and behave in the world as individuals.

Each time we kill a lion, we lose a little bit of what distinguishes us as humans: our capacity for compassion, for making rational decisions that benefit the common good, for overcoming the urge to demonstrate power and dominance at the expense of our neighbors and our environment.

If we lose our big cats, we will mourn a species that we barely understood. Only a few of us will have encountered an individual wild lion.

And this will be the greatest loss: That we knew just enough to save them, enough to change our behavior, enough to make a difference, and that we chose not to act.

Mountain lions are often known for their role as a keystone species, but they are less commonly known as an umbrella species.

While a keystone species is a species on which other species in an ecosystem largely depend, such that if it were removed the ecosystem would change drastically, an umbrella species is a species that have either large habitat needs or other requirements whose conservation results in many other species being conserved at the ecosystem or landscape level.

by Kevin Hansen

Read the book FREE online by clicking the chapters listed below.

Foreword by Robert Redford

"Mountain lions live a short 13 years in the wild -- if they make it to old age. Today, few lions live a full natural lifespan.

It's a difficult life, full of potentially lethal challenges: even when the lion avoids humans.

They are shot for recreation, for sport, and for trophies. They are shot when a rancher's livestock is lost, and when pets disappear. They are shot when people are afraid.

The cougar works a powerful magic on the human imagination. Perhaps it is envy. This majestic feline personifies strength, movement, grace, stealth, independence, and the wilderness spirit. It wanders enormous tracts of American wilderness at will. It is equally at home in forest, desert, jungle, or swamp. An adult cougar can bring down a full-grown mule deer in seconds. It yields to few creatures, save, bears and humans.

The cougar's solitary and stealthy lifestyle feeds its mystery. Unfortunately, mystery breeds fear, myth, and misinformation. Since our European ancestors first landed on American shores 500 years ago, we have waged war on large predators. The grizzly, wolf, jaguar, and cougar are now gone from the majority of their original ranges, and loss of habitat now looms as the greatest threat to the small populations that survive. Only in the last three decades have wildlife biologists begun to chip away at the fable and folklore and reveal the cougar for the remarkable carnivore that it is.

The Mountain Lion Foundation is one organization encouraging a more enlightened view of our American lion. The Mountain Lion Foundation was instrumental in the passage of the California Wildlife Protection Act of 1990, which banned the sport hunting of cougars in California and set aside $30 million a year for the next 30 years for wildlife habitat conservation. Because of their extensive range and position high in the food chain, saving land for cougars also protects land for other wildlife and plants."

Robert Redford

Cougars were roaming the Americas when humans crossed the Bering land bridge from Asia 40,000 years ago. They watched the Spanish conquer the Aztecs and the pilgrims land at Plymouth Rock. The big cats prowled the banks of the Mississippi, Colorado, and Amazon rivers. They crossed the high, windy passes of the Sierra Nevada, the Rocky Mountains, and the Andes. They witnessed the first Mormons arrive in Utah, prospectors invade the California gold fields, and gauchos herd cattle in Argentina’s pampas. From the Canadian Yukon to the Straits of Magellan – over 110 degrees latitude – and from the Atlantic to the Pacific, the cougar once laid claim to the most extensive range of any land mammal in the Western Hemisphere. (1)

That cougars can be found from sea level to 14,765 feet, (2) and survive in the dense forests of the Pacific Northwest, the desert Southwest, and Florida’s Everglades, is testimony to the big cat’s resilience and adaptability. These qualities were put to the test as never before when European explorers set foot in the Americas in the 14th century. Early colonists viewed the lion as a threat to livestock, as a competitor for the New World’s abundant game, and most importantly, as the personification of the savage and godless wilderness they meant to cleanse and civilize. Their death sentence pronounced, cougars were hunted, trapped, and shot on sight, and their habitat was stripped away as land was cleared to make way for agriculture and new towns. Today, the lion’s known range in North America has been reduced to areas in the 12 western states, the Canadian provinces of British Columbia and Alberta, and a small remnant population in southern Florida. An increasing frequency of sightings suggest that some populations may still survive in parts of the eastern United States and Canada. (3)

The cougar is listed in dictionaries under more names than any other animal in the world

THE CAT OF MANY NAMES

Because of their enormous range, cougars are known as “the cat of many names.” Writer Claude T. Barnes listed 18 native South American, and 25 native North American, and 40 English names. (4)

The cougar is listed in dictionaries under more names than any other animal in the world.. (5) The Guarani Indians of Brazil called them cuguacuarana, which French naturalist Georges Buffon corrupted into cougar.. (6,7) Puma comes from Quichua, an Inca language, meaning “a powerful animal.”. (6,8) To the Cherokee of the southeastern United States the big cat was Klandagi, “Lord of the Forest,” while the Chickasaws called him Koe-Ishto, or Ko-Icto, the “Cat of God.”. (7) In Mexico they are leopardo, to other Spanish-Americans, el Leon.. (6,7)

In 1500, Amerigo Vespucci was the first white man to sight and record a cougar in the Western Hemisphere. Vespucci, after whom the two American continents are named, was probing the coastline of Nicaragua when he saw what he described to be lions, probably because of their similarity to the more familiar African lion. (8,9) Two years later, on his fourth voyage to the New World, Christopher Columbus saw “lions” along the beaches of what are now Honduras and Nicaragua. (6,7,8) The honor of being the first European to sight a “lion” in North America fell to Alvar Nunez Caheza de Vaca, who in 1513, saw one near the Florida Everglades. (8)

Tyger was another name used for the American lion throughout the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida during the 15th and 16th centuries. (7) Today, cougar, mountain lion, and puma are the most common names used in the western United Stares, while panther, painter, and catamount are more frequently heard east of the Mississippi. Panther is the Greek word for leopard; painter is an American colloquial term for panther; and catamount is a New England expression, meaning “cat-of-the-mountains.”(10) Biologists call it Felis concolor, literally, “cat of one color.” Throughout this book, the names cougar, mountain lion, puma, and panther are used interchangeably.

Tyger was another name used for the American lion throughout the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida during the 15th and 16th centuries. (7) Today, cougar, mountain lion, and puma are the most common names used in the western United Stares, while panther, painter, and catamount are more frequently heard east of the Mississippi. Panther is the Greek word for leopard; painter is an American colloquial term for panther; and catamount is a New England expression, meaning “cat-of-the-mountains.”(10) Biologists call it Felis concolor, literally, “cat of one color.” Throughout this book, the names cougar, mountain lion, puma, and panther are used interchangeably.

FROM WHENCE CAME CATS?

The fossil record of felines is as filled with mystery as today’s cats themselves. Paleontologists and biologists have traditionally relied upon fossils and differences in physical structure of modem animals to map the evolution of a particular species. This has proven difficult with cats for two reasons: most ancestral cats occupied tropical forests, where the conditions for the preservation of fossils is poor; and most of the physical characteristics of cats are related to the capture of prey, with the result that all felines are very similar in structure. (11) As a result, no less than five different hypotheses have been offered to explain the relationships between the various groups and subgroups of extinct and modern cats. (12)

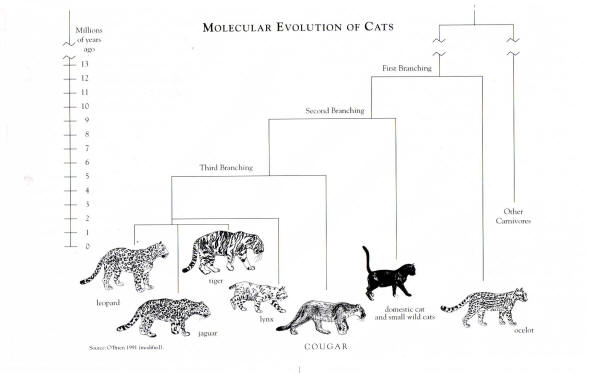

While there are differing interpretations of the evolution of the cat family (Felidae), a few facts are agreed upon. Modern and extinct carnivores have a common ancestor called Miacids. These primitive, tree-dwelling carnivores lived in the forests of the Northern Hemisphere 39 to 60 million years ago. Then, about 40 million years ago, a burst of evolution and diversification produced the modern families of carnivores. These new carnivores fall into two major groups: a bear-like group (arctoids), consisting of modem bears, seals, dogs, raccoons, pandas, badgers, skunks, weasels, and their relatives; and a cat-like group (aeluroids), a lineage including the cats, hyenas (yes, that’s right), genets, civets, and mongooses. (12)

The first cat-like carnivores to appear were the saber- tooth cats, about 35 million years ago. (11) The sabertooths became extinct about 10,000 years ago worldwide, at the end of the last glaciation. (13) While the sabertooths met their demise, however, the modem cats were evolving and diversifying. Ancestral pumas lived in North America from three to one million years ago, with modern pumas appearing about 100,000 years ago or less. (11) The American lion had arrived.

THE FAMILY OF CATS

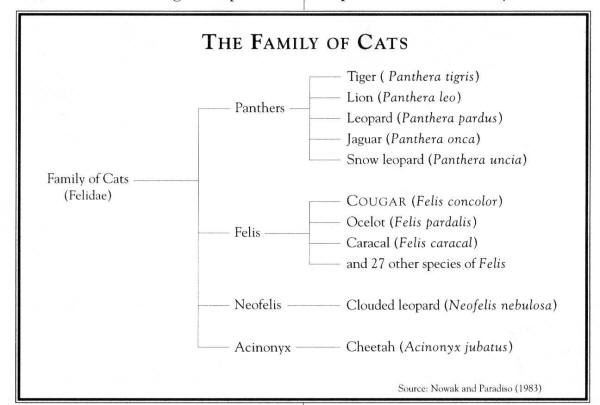

Just as there is disagreement about where cats came from, there is debate over how to classify the 37 species of cats that exist today. I discovered no less than six different proposed classification systems for Felidae during the research for this book. The Latin name Felis concolor was first given to the cougar in 1771 by Carolus Linneaus, the father of taxonomy. (It was Linneaus who devised the binomial system for describing and classifying plants and animals.)

Today, scientists generally divide the cat family (Felidae) into two groups, or genera: Panthera, the large roaring cats, and Felis, the smaller purring cats.. (11) The ability to roar depends on the structure of the hyoid bone, to which the muscles of the trachea (windpipe) and larynx (voicebox) are attached. The tiger (Panthera tigris), African lion (Panthera leo), leopard (Panrhera pardus), and jaguar (Panthera onca) represent this group. Members of Felis possess the ability to purr or make shrill, higher-pitched sounds. Of the seven cat species in North America, only the jaguar (Panther onca) belongs to Panthera. The other six – cougar (Felis concolor), lynx (Lynx canadensis), bobcat (Lynx rufus), matav (Felis wiedii), ocelot (Felis pardalis), and jaguarundi (Felis yagouaroundi) – are purring cats and are members of Felis.. (14) The cougar is the largest of the purring cats.

Today, scientists generally divide the cat family (Felidae) into two groups, or genera: Panthera, the large roaring cats, and Felis, the smaller purring cats.. (11) The ability to roar depends on the structure of the hyoid bone, to which the muscles of the trachea (windpipe) and larynx (voicebox) are attached. The tiger (Panthera tigris), African lion (Panthera leo), leopard (Panrhera pardus), and jaguar (Panthera onca) represent this group. Members of Felis possess the ability to purr or make shrill, higher-pitched sounds. Of the seven cat species in North America, only the jaguar (Panther onca) belongs to Panthera. The other six – cougar (Felis concolor), lynx (Lynx canadensis), bobcat (Lynx rufus), matav (Felis wiedii), ocelot (Felis pardalis), and jaguarundi (Felis yagouaroundi) – are purring cats and are members of Felis.. (14) The cougar is the largest of the purring cats.

A different approach to the evolutionary and taxonomic puzzle of feline classification was taken recently through the application of the new science of molecular evolution. By examining the rate of change of the genes in the DNA molecules of different cat species. biologist Stephen J. O’Brien and his colleagues revealed that the 37 species of modern cats evolved in three distinct lines. The earliest branch occurred 12 million years ago and includes the seven species of small South American cats (ocelot, jaguarundi, and others). The second branching took place 8 to 20 million years ago and included the domestic cat and five close relatives (Pallas’s cat, sand cat, and others). About 4 to 6 million years ago a third branch split and gave rise to the middle-sized and large cats. The most recent split (1.8 to 3.8 million years ago) divided the lynxes and the large cats. This third line gave rise to 24 of the 37 species of living cats, including the cougar, cheetah, and all big cats. (15)

The differences of these two classification systems are apparent and are representative of the disagreement among experts. Some biologists believe we have progressed as far as we can in our understanding of feline taxonomy through the examination of museum specimens, and that future answers lie in the study of behavior, ecology, and genetics.. (16) For instance, a cheetah-like cat existed in North America less than a million years ago, but was extinct by the end of the Pleistocene era (10,000 years ago). It evolved in parallel with the modern African cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) and was similar in appearance; however, it appears to have been more closely related to the living cougar than to the cheetah.. (11,13) Resolving where cougars fit into the cat family would give us one more piece of the puzzle of how the American lion came to be.

The differences of these two classification systems are apparent and are representative of the disagreement among experts. Some biologists believe we have progressed as far as we can in our understanding of feline taxonomy through the examination of museum specimens, and that future answers lie in the study of behavior, ecology, and genetics.. (16) For instance, a cheetah-like cat existed in North America less than a million years ago, but was extinct by the end of the Pleistocene era (10,000 years ago). It evolved in parallel with the modern African cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) and was similar in appearance; however, it appears to have been more closely related to the living cougar than to the cheetah.. (11,13) Resolving where cougars fit into the cat family would give us one more piece of the puzzle of how the American lion came to be.

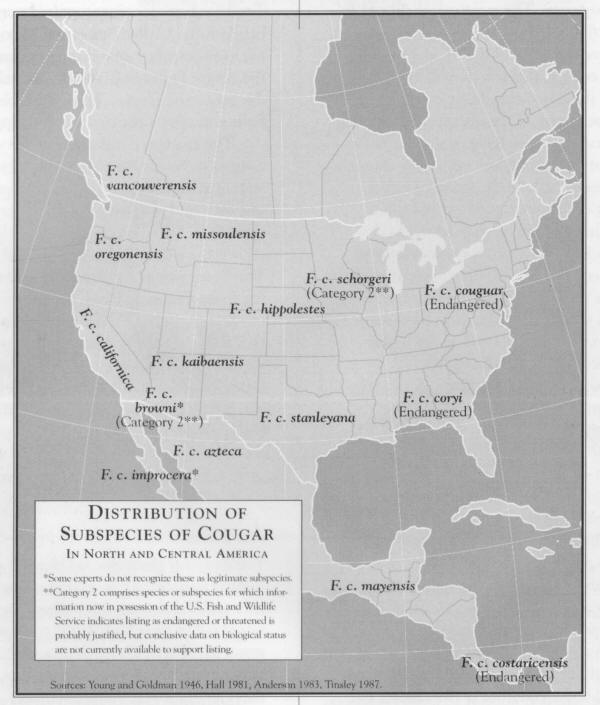

SUBSPECIES AND STATUS

When a species is as broadly distributed as the cougar, regional variations in physical appearance occur. For instance, mountain lions from Alberta look somewhat different than the Florida panther, a fact that relates to the different geographic habitats in which the lion lives. (17) Wildlife taxonomists recognize these regional variations by dividing Felis concolor into some 26 subspecies or geographic races, scattered across North and South America. (18) This is similar to the different races or breeds of the domestic dog. Edward A. Goldman, coauthor of the classic, The Puma: Mysterious American Cat, explains how the subspecies of cougar are classified: “The subspecies or geographic races of the puma, like those of other animals, are based on combinations of characters, including size, color, and details of cranial [skull] and dental structure(6) Twelve subspecies are recognized north of the border between the United States and Mexico. (6,7,18) (When writing the scientific name of a particular subspecies, such as the cougar found in Colorado, the subspecies name follows the genus and species. Thus, the Colorado cougar becomes Felis concolor hippolestes or F. c. hippolestes.)

The existence and status of the various subspecies of cougars in North America is the subject of heated debate among academics and wildlife professionals.

The existence and status of the various subspecies of cougars in North America is the subject of heated debate among academics and wildlife professionals. The two subspecies found in eastern North America, the eastern panther (Felis concolor couguar) and the Florida panther (F. c. coryi), are classified as endangered and fully protected. (19) The Yuma puma (F. c. browni), a subspecies found along the lower Colorado River, is currently a candidate for listing as endangered. (20) While cougar populations are considered to be healthy in many parts of western North America, populations adjacent to rapidly expanding urban areas are facing critical habitat loss. In southern California for example, mountain lions in the Santa Monica Mountains and Santa Ana Mountains are fast losing ground to rampant residential development.

APPEARANCE AND SIZE

The cougar is plain-colored like the African lion, but is of slighter build with a head that is smaller in proportion to its body. Male pumas do not have the distinctive mane and tufted tail of their Old World cousins. (2) The absence of a mane led to an early myth about mountain lions: Early Dutch traders in New York were puzzled that the lion skins they obtained were those of females Only. They questioned Indian hunters and were assured that such animals existed, but only in the most inaccessible mountainous places, where it would be foolhardy to attempt to hunt them. (1)

Except for the smaller jaguarondi of Central and South Americas, the cougar is the only plain-colored cat in the Americas. (2) The sides of the muzzle and the backs of the ears are dark brown or black, while the chin, upper lip, chest, and belly are creamy white. (21) Atop the small head sit a pair of short, rounded ears. The cougar’s long and heavy tail is perhaps its most distinctive feature. Measuring almost two-thirds the length of the head and body, it is tipped with brown and black. Cougars are the largest native North American cat except for the slightly larger jaguar (Panthera onca), which is occasionally found in the southwestern United States. (22) The sexes look alike, though males are 30 to 40 percent larger than females. (23) The largest animals are found in the northern and southern extremes of its range. Though sizes vary greatly throughout the cat’s geographic range, a typical adult male will weigh 110 to 180 pounds and the female 80 to 130 pounds. Exceptional individuals have exceeded 200 pounds, but this is rare. Males will measure 6 to 8 feet from nose to tail tip and females 5 to 7 feet. (2)

Cougars are the largest native North American cat except for the slightly larger jaguar (Panthera onca), which is occasionally found in the southwestern United States. (22) The sexes look alike, though males are 30 to 40 percent larger than females. (23) The largest animals are found in the northern and southern extremes of its range. Though sizes vary greatly throughout the cat’s geographic range, a typical adult male will weigh 110 to 180 pounds and the female 80 to 130 pounds. Exceptional individuals have exceeded 200 pounds, but this is rare. Males will measure 6 to 8 feet from nose to tail tip and females 5 to 7 feet. (2)

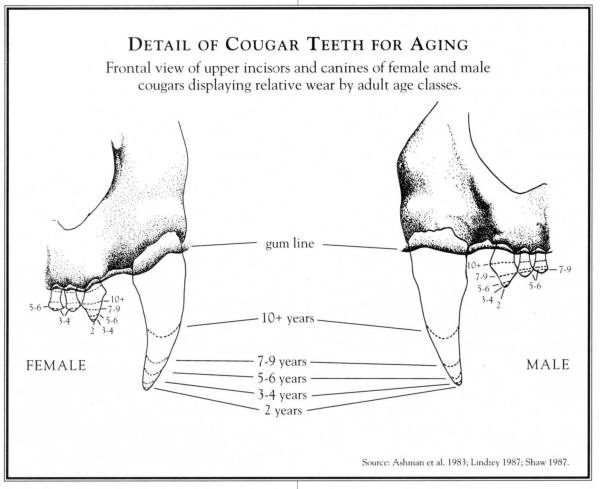

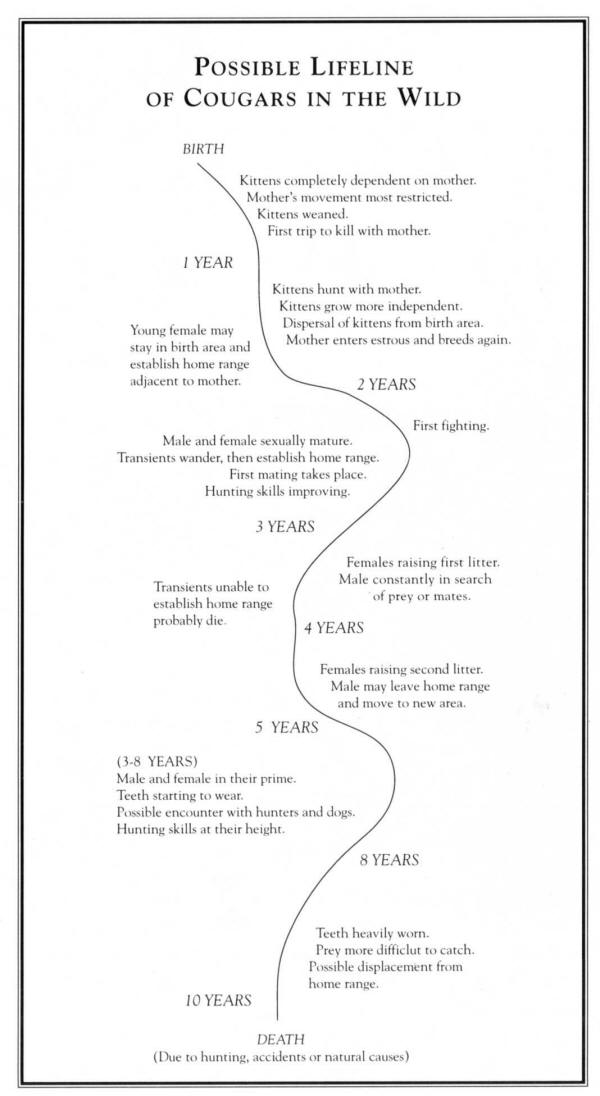

In captivity, cougars have lived as long as 21 years. (24) In the wild, the cats probably live only half as long. Lack of a reliable way to determine a mountain lion’s age makes exact measurements difficult. In the wild, a 10-year-old lion is likely a very old cat. Experts also disagree over which gender lives longer on the average. Some think the added stress of raising kittens guarantees female lions a shorter life. The lifespan of both sexes in hunted populations is probably shorter. (25) But, even in the absence of hunting, a short life span is to he expected of a predator that faces the frequent hazards of feeding on prey much larger than itself.

Cougar The American Lion Line Illustrations

Copyright (1992-2009) by Linnea Fronce

CHAPTER NOTES

Pregnant females do not prepare elaborate dens. It seems matter that it provides a refuge from predators (coyotes, golden eagles, other cougars) and shields the litter from heavy rain and hot sun. Dens rarely contain any bedding for the young, though a mothers soft belly hair was found in one.(2)- (This also contradicts the popular misconception, perpetuated largely by some nature movies, that cougars always choose caves as dens.)(6)

Newborn mountain lions enter the world as buff brown balls of fur weighing slightly more than a pound.(1) Biologists call them kittens or cubs either is correct. Their eyes and ear canals are closed, their coats are covered with blackish brown spots, and their tails are dark-ringed.(2) This color pattern provides excellent protective camouflage.

Kittens begin nursing within minutes after birth and gain weight rapidly, with males tending to outpace females.(1) Nursing mothers have eight teats but apparently only six produce milk. Kittens start to compete for nipples the first day and generally suckle the same nipple whenever nursing.(4) At two weeks of age the kittens’ eyes and ears are opened and they are able to walk. Within 10 to 20 days the kittens may weigh over two pounds. They begin to move awkwardly about, exploring the rock overhang, brushy thicket, or pile of boulders that serves as their den.(5)

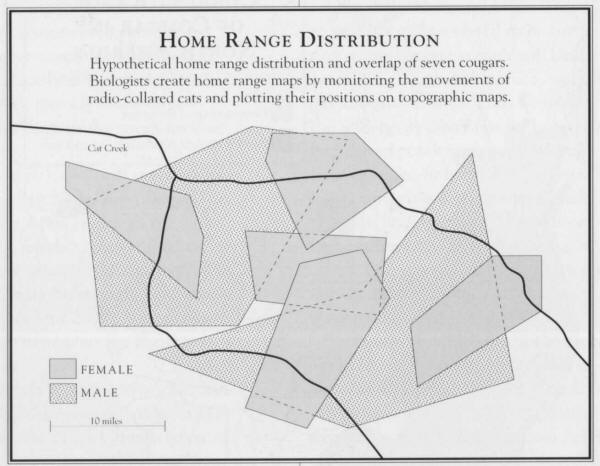

While suckling her young the mother must occasionally leave the den to hunt. This is the time of her most restricted movement, because she does not want to venture too far from her vulnerable kittens. Still, she must hunt to sustain herself and replenish her milk. While hunting the female cougar remains within a fixed area called a home range. Varying in size from 25 to 400 square miles,(7,8) home ranges are restricted areas of use in which cougars confine their movements while hunting, searching for a mate, or raising young. Biologists refer to the cougars that occupy home ranges as residents. Possession of a home range is critically important to a female cougar because it increases her litter’s chances for survival by guaranteeing an established hunting area for the mother.

…kittens learn early to move around their range and not imprint upon a single home site.

By the time kittens are weaned at 2 to 3 months, the mother has moved the litter to one or more additional den sites throughout her home range. This provides greater protection for the young and may be one reason she does not construct elaborate dens. In his book Soul Among Lions, Arizona cougar specialist Harley Shaw explains that there are other advantages to such behavior: “…kittens learn early to move around their range and not imprint upon a single home site. Home is the entire area of use. Within it, lions are free to move, hunt, and rest as their mood and physiology directs. They are not handicapped the human compulsion to return to a single safe base at night. Home is a large tract of land that they undoubtedly come to know as you and I know the floorplan of our house. They learn to be lions in this home area.”(6)

The physical metamorphosis of young, growing cougars is dramatic, especially their teeth and coat. Teeth are critical to a cougar’s survival, so the teeth in young cougars develop quickly. Their large canines (or fangs) allow them to capture and kill prey, while their specially adapted molars (called carnassials) are used to cut through tissue while feeding. Canines first appear at age 20 to 30 days, followed by the molars at 30 to 50 days. Permanent teeth start replacing primary (baby) teeth at about 5 1/2 months. The permanent canines first appear at month eight, and for a short time both permanent and primary canines are present.(3)

As an adult cougar’s tawny coat provides camouflage while stalking prey, a kitten’s spots provide camouflage from predators. Kittens begin to lose these spots at 12 to 14 weeks, they fade rapidly but are still obvious at 8 months, less so at one year. By 15 months the markings are visible only on the hindquarters and only under certain light conditions. In some cougars, the stripes on the upper foreleg are still visible at 3 years of age.(3,9)

The mountain lion’s coat is not the only feature that changes color with age. Their eyes, light blue at birth, begin to change at four months and are the golden brown of adults by 16 to 17 months.(3,9)

GROWING UP AND LEAVING HOME

Female cougars probably begin leading their kittens to kills as early as 7 to 8 weeks. The mother also carries meat to her young from kills until weaning age (2 to 3 months), at which point the cubs weigh in at between 7 and 9 pounds. As the kittens grow older, the mother will leave them at kills, frequently for days at a time, while she goes in search of the next prey.(6) As the kittens grow and become stronger, the mother will range farther in search of prey.

Biologists have frequently noted how intensely a female with kittens uses her home range. This is most concentrated subsequent to birth, then expands as the kittens are able to accompany her to kills. It’s easy to imagine an insistent mother as she drags, pushes, and urges her kittens along over the many miles between kills. She expends an enormous amount of energy feeding her growing litter. As a result, the density of prey in the mother’s home range affects how well she can provide for her young, which in turn influences their likelihood of survival.

Arrival at a kill is a time of both feeding and play for kittens. Vegetation is frequently disturbed for 50 feet surrounding the carcass. Grass is flattened, limbs are broken off trees and trunks are covered with the kittens’ claw marks. The carcass is more fully consumed than it would be by an adult lion alone, and pieces of hair and bone are scattered about. This rambunctious play by the young at a kill is another part of their training as predators. They will stalk, attack, and wrestle with their siblings or mother, as if they were the next meal rather than their own flesh and blood. Ultimately, though, play gives way to the real thing.

As they grow stronger and more skilled at stalking, kittens will separate from their mother for days at a time and hunt on their own. This growing independence is a precursor to young lions leaving their mother and going in search their own home range. Biologists are not certain whether a mother and her young gradually grow apart, with the kittens gradually leaving of their own accord, or whether she abandons them as do female black bears with their young. Sonny Bass has found the latter to the case in Florida. “My experience with Florida panthers in the Everglades based on daily tracking) indicates that the mother leaves the young.”(10) Seidensticker tells of one Idaho cougar that abandoned her kittens at a kill.(11) Paul Beier, who studied mountain lions in southern California, believes the mother discourages her kittens from remaining with her. “Some sort of agonistic behavior on the part of the mother is necessary to discourage the young from staying. Simply abandoning the young is not possible because they know where to find her.”(12) The presence of mature resident males attracted to the female, who by now is in heat, may also discourage the young from remaining. However they separate, the kittens are finally on their own and the mother will come into heat and breed again.(6)

Kittens can survive on their own as early as 6 months, such as when the mother is killed or dies of natural causes, but this appears to be rare. Typically, the young cougars will remain with their mother for 12 to 18 months. This allows them to hone their hunting skills and gives them time to develop their killing bite.(14) This bite is usually delivered to the back of the neck of large prey, severing the spinal cord and causing almost immediate death. To be executed efficiently, the bite requires practice and development of the cougar’s powerful jaw muscles. Evidence seems to indicate that the behavioral patterns of killing prey may be innate, but that selection of appropriate prey and stalking may require practice to acquire the necessary skill.(1,2,6) This may explain why young cougars are sometimes found with a face full of porcupine quills, or are the culprits in attacks on domestic livestock.

The departure of young cats from their mother’s home range is called dispersal, and it is a time when the young cougars are especially vulnerable; they expose themselves to the dangers of taking prey without the alternative of food provided by their mother. These young cats called transients, wander far from the familiar home range of their mother and their hunting skill are not as efficient as those of older resident cats. The dispersal ot young transient cougars out of their birth areas is crucial, however, as it reduces inbreeding and provides new blood to outlying populations.(9)

MATING

Both male and female cougars are sexually mature at 24 months, but females have been known to breed as early as 20 months;(9) a Florida panther was recently reported as having given birth before she was 2 years old.(15) The age of the first breeding may be delayed until the female has established a home range.(16)

When it comes time to mate, the first challenge facing a male and female cougar is finding each other. Solitary and territorial by nature, cougars are frequently scattered over hundreds of miles of rugged terrain. It further complicates the matter that females are receptive to males for only a few days out of each month;(17) however, it appears to be the lions’ territorial habits and keen senses that ultimately allow them to come together.

Polygamy seems to be the rule for both male and female mountain lions. Males occupy larger home ranges than females, and a resident male with a large home range typically overlaps or encompasses the home ranges of several resident females. Nevertheless, in stable cougar populations with established home ranges, females rarely mate with more than one resident male during a breeding cycle.(9)

Resident male cougars use scrapes as visual and olfactory signals to other cougars and to mark their home range area. A scrape (or scratch) is a collection of pine needles. leaves, or dirt scraped into a pile with either the forepaw or hindpaws. Occasionally they urinate or defecate on the pile. Scrapes are made throughout the home range and are frequently located along travelways under a tree(18,19) or along ridges. Females rarely scrape, more commonly burying their feces under mounds of dirt and debris; these mounds are usually found near large kills.(19)

Mountain lion authority Fred Lindzey believes scrapes help mountain lions both avoid and locate each other. “Scrapes are definitely a means of communication. They broadcast the resident male’s presence to other males (residents and transients) and to females. Females may use scrapes made by the resident male to both avoid him when she has dependent kittens and to find him when she is in estrus.”(20)

Adult males probably spend most of their time searching for receptive females.(21) When mating does occur, it usually takes place in the female’s home range, with the male seeking out the female.(6) The female’s estrous cycle lasts approximately 23 days and she is usually in heat for about 8 days. The pair may stay together for up to 3 days, sometimes even sharing a kill.(19)

Cougars compensate for long periods of solitude with some of the most vigorous breeding behavior known to exist among mammals. Copulation can occur at a rate of 50 to 70 times in 24 hours for a 7- to 8-day period.(22) Each copulation lasts less than a minute.(2) Such enthusiastic copulation in is thought to stimulate ovulation, (the release of eggs from the ovaries to make them available for fertilization). In his book The Natural History of Wild Cats, Andrew Kitchener explains the advantage of such behavior: “Most cats are thought to be induced ovulators, so that even though the female may come into estrus, no ovulation occurs unless the vagina and cervix of the female are stimulated repeatedly during mating. As a consequence of estrus lasting several days and ovulation being induced, the chance of a successful fertilization can he maximized.”(23) Some biologists speculate that high copulation rates also evolved as a way for females to evaluate male vigor(1) and to ensure that their offspring receive the best genetic endowment.(24)

Cougars appear to be as vocal as they are enthusiastic during mating. The “caterwaul,” characteristic in domestic cats, seems to be even louder in mating cougars. Such behavior has been documented both in captive and wild cougars.(9) Paul Bier has heard these sounds coming from mating cougars in his California study area;(12) biologist Susan de Treville, who studied mountain lions in California, was camping on the Malaspina Peninsula in British Columbia when the heard two cougars mating nearby. “Both were screaming loudly. They got to within a foot of my tent, then they gradually moved off. In the morning I found the ground torn up and all the grass flattened.”(25)

After 88 to 96 days, the mother retires to the seclusion of the den and gives birth to a litter of 1 to 6 kittens (or cubs). The average litter size is 2 to 3 kittens, but a young female may produce only 1 kitten in her first litter. This seems to reduce the stress on first-time mothers, allowing them to develop their skills in rearing young. Since cougars tend to bear young every other year, a female that lives for 8 to 10 years has the potential to produce 5 litters. One captive cougar produced 7 litters in 16 years.(27) How many of the kittens survive to adulthood is still a mystery. It is also unknown if the number of offspring produced by a female cougar fluctuates in relation to the abundance of prey, as in other predators such as coyotes and barn owls. Few newly born litters have been studied closely in the wild and definitive information is lacking; however, current research underway in Yellowstone National Park and in the San Andres Mountains of New Mexico may provide some answers about the early lives of pumas.

If a female loses her kittens to predators or other circumstances, she may begin her estrous cycle and breed again soon after the loss.(28) Sometimes, predators include male cougars; studies in Idaho, Utah, and California have documented that males do indeed kill and even eat kittens on occasion. Whether this is an evolved behavior similar to African lions is unknown, but it may partly explain why females with kittens are unreceptive to males and intolerant of their presence until the young are independent and can hunt for themselves. Females also seem to possess the ability to suppress their estrous cycle during the period they are raising young. Some experts speculate that this ability is hormonal in nature and is possibly related to lactation; others suggest that estrous cycles continue normally and the female simply works harder at avoiding males by being careful where she urinates and by burying her feces. Whether this behavior is hormonal, behavioral, or both is unknown.

Unlike most wild animals, cougars can and do give birth throughout the year, although peaks have been documented in different parts of their range. One population in Idaho peaked in the spring,(16) while cougars in parts of Utah and Wyoming(29) had fall birth peaks. Nevada biologists documented birth peaks during June and July and noted 70 percent of all births occurred between April and September.(9) Mountain lions in and around Yellowstone National Park give birth primarily in midsummer.(30) Researcher Allen Anderson looked at the birth dates of 6 wild and 35 captive cougars and discovered that over half (55 percent) of the births occurred during April, June, July, and August.(1)

Biologists long speculated that in temperate climates, births occurring during the warmer months placed less stress on both the mother and kittens; however, as Harley Shaw points out, “Birth in warm months forces the mother to be feeding large young during mid to late winter. This does not reduce stress on her over the long haul.”(31) It has also been suggested that in the warmer climates of Arizona, Florida, and California, births may be more evenly distributed throughout the year. Existing information from these states is inconclusive. Two more aspects of the American lion that have left experts scratching their heads.

DEATH

While all cougars enter the world in the same fashion, they leave it in a variety of ways. Existing information indicates that the three primary causes of cougar deaths are humans, natural causes, and accidents.

More mountain lions die at the hands of humans than any other known cause of death. This is as true today as it was in the past. A minimum of 65,665 cougars were shot, poisoned, trapped, and snared by bounty hunters, federal hunters, and sport hunters from 1907 to 1978 in the 12 western states, British Columbia, and Alberta.(32) This carnage seemed to peak between 1930 and 1955, with the highest numbers of pumas killed in California, British Columbia, and Arizona.(1) This sobering tally does not include the thousands of cougars slaughtered prior to the 1900s nor the untold numbers that have gone unreported since.

Today, cougar hunting is legal in Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Texas, Utah, Washington, Wyoming, and the Canadian provinces at British Columbia and Alberta. During the 1989-1990 sport harvest season more than 2,176 cats were killed.(33) Most of these states allow hunters to kill only one lion per season with the notable exception of Texas, which has the most liberal hunting regulations and places no limits on the number of cats a hunter can take. The cougar enjoys full protection in 24 states and provinces, but has no legal classification and no protection, except in agreement with the Federal Government, in 22 other states and provinces. (3,32)

Predator control programs present yet another obstacle to the cougar’s survival. The U. S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal Damage Control (ADC) program was responsible for killing 207 cougars in 11 western states during the 1988 fiscal year because of attacks on domestic livestock.(34)

In addition to ADC’s efforts, many states carry on their own predator control programs. For instance, in 1988, ADC killed 38 cougars in California, while the state Department of Fish and Game authorized other hunters to take an additional 28 cougars on depredation permits, for a total of 64 cats. This situation is further complicated by the fact that cougars are occasionally caught in traps set for other animals, and because there is no easy way to release them many are killed. The cats can sometimes pull themselves free of the traps, often at the cost of severed toes or broken bones. Cats that escape with minor injuries may still be capable of taking large prey and surviving, while those with debilitating injuries likely die of starvation.(9)

Collisions with motor vehicles are the primary cause of death in Florida panthers.

Collisions with motor vehicles are the primary cause of death in Florida panthers. From 1979 to 1991, almost 50 percent of documented mortality of the Florida cats was due to collisions with autos.(35) In California, 22 mountain lions fell victim to collisions between 1971 and 1976,(7) while researcher Paul Beier lost five lions he was studying to cars.(12) Three young cougars were even killed by a train, all in the same incident, in Colorado.(1)

A number of the cats have drowned in irrigation canals,(36) or by falling into wells.(37) Cougars are capable swimmers, but the smooth concrete banks make escape difficult and the exhausted cats will eventually drown. Unfortunately, such incidents will increase as more cougar habit is encroached upon by humans.

Other types of accidents include falls from cliffs, being struck by lightning, being hit by rock slides, being poisoned by venomous snakes, and choking.(3) Susan de Treville tells of a mountain lion that died from a violent encounter with a manzanita bush. “We were monitoring an old lion (9-10 years) named Snaggletooth, because he had a broken upper canine. One day we found him lying in an open field-dead. We had no idea what killed him. Later an examination revealed a 5-inch piece of manzanita in the cat’s throat. Apparently, during the final rush at what we think was a deer, the cat ran into a manzanita bush at high speed driving a stab down its throat and severing the carotid artery. Failing eyesight may have been part of the reason Snaggletooth bled to death internally.”(25)

There are three times during their lives when cougars are most at risk: immediately after birth, immediately after becoming independent transients, and during old age.(3) Kittens left alone at a den or kill are vulnerable to other predators, including, as has been noted, adult male cougars; it is unknown how many kittens survive to maturity, but experts suspect that kitten deaths could equal or exceed the number of cougars killed by sport hunting. Transient cougars spend most of their time in unfamiliar territory and have not honed their hunting skills, so do not hunt as efficiently as resident cougars. Old cougars experience extreme tooth wear and loss in weight, making them less efficient hunters, resulting in starvation. Old age is probably the most significant cause of death in unhunted mountain lion populations; a recent study in southern Utah showed that the annual mortality rate in an unhunted cougar population was a fairly high 26 percent. (26) In Montana’s hunted cougar populations, over 50 percent of the resident adults in one area were killed, according to research conducted there.(40)

Adult cougars do kill and even eat one another on occasion.(1) Fighting has been documented in Arizona, California, Nevada, Texas, Wyoming, and Utah. In one study in the San Andres Mountains of southern New Mexico, fighting was found to the primary cause of death.(41) While in Florida, fighting has led to the death of six endangered panthers over the past 11 years. Of these, two were transient males dispersing from their mother’s home range through home ranges of resident males courting females in heat; two were adult females killed by a young adult male; and the last two were the result of fighting between adult males.(35) Experts speculate that most conflicts are over females and home ranges, but it is still unknown precisely how much fighting contributes to overall mortality in a cougar population.

Cougars appear to suffer from relatively few internal and external parasites. Those they do contend with include an assortment of fleas, ticks, mites, and tapeworms. The puma’s solitary lifestyle and its habit of spending little time in dens probably minimizes infestation.(2,3)

Deaths attributable to more serious diseases appear to be uncommon. Only two cases of rabies have been documented in wild mountain lions, one in California in 1909,(42) and a more recent case in Florida.(35) Naturally occurring antibodies to feline distemper were found in 85 percent of the Florida panthers tested.(43) Another mountain lion in California was recently diagnosed with feline leukemia and was killed. California Department of Fish and Game veterinarian Thierry Work thinks the cat may have been infected by eating domestic cats. The feline leukemia virus is frequently fatal and no vaccine for wild cougars exists; this disease especially threatens small, isolated populations of cougars that front on urban areas, such as in southern Florida and southern California. Allen Anderson cautions that the widely held opinion that wild pumas are largely free of parasites and diseases may be due to the lack of specific research rather than reality.(1) Cougar diseases are just one of many aspects of the cat that need further study.

Cougar The American Lion Line Illustrations

Copyright (1992-2009) by Linnea Fronce

CHAPTER NOTES

WHERE COUGARS LIVE

Biologists marvel at the cougar’s remarkable adaptability. The best example of this is the cat’s enormous geographic range. Cougars seem equally at home in Alberta’s alpine forests, Arizona’s Sonoran Desert, or Mexico’s tropical jungles. While the lions don’t seem particular about where they live, studies show that the cats do prefer certain types of terrain and vegetation. Habitat, a space and an environment suited to a particular species, and geographic range, a broader term indicating the map area in which a species occurs, are important concepts in understanding cougar life.(1) One expects to find cougars only in suitable habitats within a geographic range, and suitable cougar habitat contains two elements: cover and large prey.

Mountain lions are stalking predators that must get close to their prey before ambushing from a short distance. They will take advantage of terrain (steep canyons, rock outcroppings, boulders) or vegetation (dense brush, thickets) to remain hidden while stalking. Cover refers to this combination of terrain and vegetation that allows the cat to stay out of sight while hunting and stalking; habitats that have good stalking cover attract mountain lions. Cover also helps protect the female cougar’s vulnerable kittens. (In The Cycle of Life Chapter I explained how a dense thicket or pile of boulders is used as a den. This is what we mean by protective cover.)

Even the best stalking cover is of no value, however, if there is nothing to stalk. Deer are the lion’s primary prey-mule deer in western North America and white tailed deer in eastern North America(2)-and deer must be present in sufficient numbers in the lion’s habitat for the cat to survive.(3) While lions will take a variety of prey, killing one deer is more energy-efficient than killing several rabbits or squirrels, allowing the cat to procure a lot of fresh meat at once. This is particularly important to females with hungry kittens to feed. Since the presence of cougars in an area is largely dependent on the presence of deer, it is important to understand what makes up good deer habitat.

Like cougar habitat, suitable deer habitat must contain a combination of cover and food. But because deer are ungulates (hoofed, plant-eating mammals) they use both resources differently. Where the puma requires stalking cover, deer need escape cover, usually a dense tangle of vegetation into which predators cannot easily follow.(1) In the case of desert bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis), on which cougars occasionally prey in New Mexico, Nevada and California, escape cover may not be “cover” in the normal sense, but a sheer rock face. The steep incline and exposure discourages a cougar from following and allows the sheep to escape.

Other types of cover are required. Deer need cover for giving birth to fawns and for resting (protective cover and resting cover). They cope with seasonal temperature extremes by taking refuge in timber stands (thermal cover); tall trees with dense foliage reduce heat loss through radiation on cold, clear winter nights, provide shade on hot sunny days, and serve as shields from strong winds for deer and cougars alike.(4)

Being herbivores (plant-eaters), deer will gravitate to habitats that have adequate forage. Mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), the most common species of deer in the western United States and Canada, require a mix of food types(5) and are known to eat 788 plant species.(6) In southern Utah, mule deer feed extensively on bitterbrush and Gambel oak, two plants that also provide excellent cover. Not surprisingly, areas dominated by these two plants are also frequented by mountain lions.(7)

Maurice Hornocker(8) and later John Seidensticker and his coworkers studied cougars in the remote wilderness of the Idaho Primitive Area (now the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness). There, they found that cougars referred steep, rocks areas covered with dense stands of Douglas fir and ponderosa pine, with sagebrush and grasslands mixed among the bluffs and talus slopes. The big cats avoided crossing large open areas with insufficient cover, preferring to travel around the perimeters.

Researchers Kenny Logan and Larry Irwin(10) studied cougars in the Bighorn Mountains of northern Wyoming; their work provided the first quantified evaluation of cougar habitat use, and their findings were similar to those of Seidensticker and Hornocker in Idaho. The cats frequented canyonland habitats with steep, rugged slopes (greater than 45 degrees) containing mixed conifer and brushy mountain mahogany cover. Grasslands and sagebrush areas with gentle slopes (less than 20 degrees) were generally avoided.

The late Steven Laing was a member of a team of researchers who studied cougars in the Boulder-Escalante region of south-central Utah. This 10-year study, completed in 1989, is considered to be the most thorough examination of the cats yet completed. Laing, being responsible for examining cougar habitat use, found that cougars selected pinyon-juniper woodlands with lava boulders scattered in the understory cover (ground vegetation). The cats also frequented ponderosa pine/oak brush, mixed aspen/spruce-fir, and spruce-fir habitats. They avoided sagebrush bottomlands, agricultural and pasture lands, slickrock sandstone canyons, and open meadows. These areas were typically at higher elevations with steeper slopes and denser understory cover. This combination of terrain and vegetation seems to enhance the cat’s ability to survey and move through the landscape unseen.(7)

Harley Shaw observed a similar pattern in Arizona. Forested areas such as those found on the Mogollon Rim and Kaihab Plateau have little understory cover and hold relatively, low mountain lion densities, while chaparral and pinyon-juniper vegetations, which have dense understory cover, have higher densities of mountain lions. Shaw suspects understory cover for stalking is the key to habitat suitability.(11)

Cougars cannot successfully take prey if there is too much or too little cover.

Seidensticker and his colleagues(9) described suitable cougar habitat as a combination of vegetation, topography, prey numbers, and prey vulnerability. Prey vulnerability refers to the ease a prey species may be captured and killed by cougars and depends on the availability of cover (both stalking cover and escape cover) and the behavior of the prey. The relationship between vegetation and prey vulnerability is particularly important: cougars cannot successfully take prey if there is too much or too little cover. The best vegetation for stalking cover is moderately dense-thick enough for the lion to remain hidden, sparse enough for the cat to see its prey.(12) Thus, the presence of moderately dense stalking cover in a habitat increases the vulnerability of the prey found there. This also explains why dense vegetation is attractive to deer as escape cover-it reduces their vulnerability to cougars.

Writer Barry Lopez (a MLF Honorary Boardmember) calls the cougar “a dweller on the edge.” Edges, or ecotones, are transitional borders between different habitat types-the places where forest meets clearing, where rocky ledge meets bush, and where willow thicket meets streamside banks.(2,13) Such areas provide good forage and cover for deer, which in turn attracts cougars. Florida panthers make frequent use of ecotones in Everglades National Park;(14) much of the panthers’ habitat in that part of south Florida is slash pine woodland s with dense understory cover of saw palmetto. This woodland forms the eastern boundary of a flat, grassy wetland (the Everglades) dotted with islands of hardwood trees called hammocks. Panthers do most of their hunting and make most of their kills along the edges of these hammocks and in these woodlands. Laing found a similar pattern in the Boulder-Escalante study: “Riparian zones [streamside habitats] and rock ledges were the two ecotones most associated with highly used areas suggesting habitat selection based on prey densities, cover diversity, and possibly water availability.” (7)

To a cougar, vegetation shape and density seems to be more important than vegetation type in determining habitat suitability. This partially explains the cat’s ability to occupy such an extensive range and variety of habitats.(12)

So the best deer and cougar habitats appear to be forested areas that contain good deer forage and cover as well as a diversity of terrain and sufficient stalking cover. Cougars seem consciously to select cover and terrain that allow them find prey, observe it while stalking, and approach close enough to make a kill.(4) Seidensticker’s study in Idaho(9) showed that, over a span of years, kill sites were clustered in certain areas, which suggested that these areas offered advantages in taking prey.

HOME RANGE

Within mountain lion habitat, adult cougars space themselves out and confine their movement to individual fixed areas known as home ranges. Home range should not be confused with geographic range, which is a broader term indicating the entire map area in which cougars occur.(1) Cougar home ranges include hunting areas, water sources, resting areas, lookout positions, and denning sites where kittens or cubs can be safely reared. Cougars that occupy home ranges are called residents, and possession of a home range enhances a resident’ lion’s chances of more consistently finding prey, locating mates, and successfully rearing young.(15)

Possession of a home range is fundamental to the cougar’s survival as a solitary predator. By having a fixed area of land to hunt in, the cougar is better able to consistently locate prey. It roams its home range constantly, learning the terrain, where the best cover is, where the deer most likely can be found. This is why survival for a transient cougar is more precarious than that of a resident cougar. Transients are constantly moving through unfamiliar territory and have not yet perfected their hunting skills.

Cougars are not territorial in the sense that they defend their home ranges to exclude all other cougars. Rather, the big cats have evolved a land tenure system(9) in which home ranges are maintained by resident lions but not transient lions. Male home ranges are typically larger than female home ranges, usually overlapping or encompassing several of the female ranges, but only occasionally overlapping those of other resident males; however, female home ranges commonly overlap. Exceptions to this pattern do exist. Studies in the Diablo Mountains of California(16) and the San Andres Mountains of New Mexico(17) showed overlap between male home ranges, while those of females did not.

In areas where home ranges overlap, cougars seem to avoid each other.

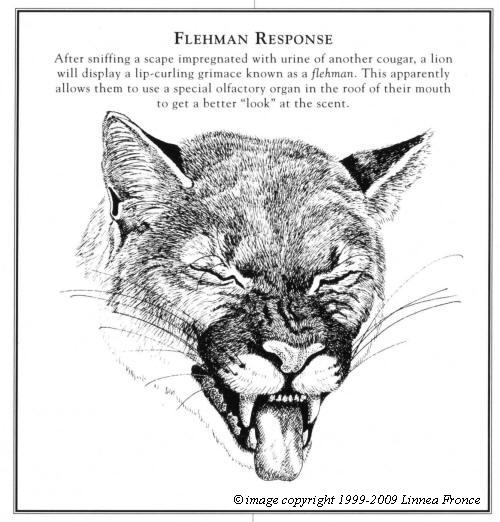

In areas where home ranges overlap, cougars seem to avoid each other. This mutual avoidance is thought to be accomplished primarily through sight and smell.(2, 12) Smell is employed through the use of scrapes. In the “Cycle of Life” chapter it was explained how scrapes function as biological traffic signals within home ranges. By either making a scrape or sniffing the scrape of other individuals, cougars send and receive a variety of messages. Male residents can announce their presence, transient lions or females with dependent kittens can avoid male residents, and females can find males when they are ready to mate.(18) Two cougars in overlapping home ranges can both use the common area because scrapes allow them to use the area at different times.

After sniffing a scrape impregnated with the urine of another cougar, a lion will display a lip-curling grimace known as a flehman. This action is thought to allow them to use a special olfactory organ in the roof of their mouth to evaluate, or get a better “look” at the scent. Biologists speculate that males may use the flehman to determine from a female’s urine whether she is ready to mate.(9,19,20) Both Seidensticker(9) and Lindzey(18) have observed this behavior in captive mountain lions.

Experts speculate that land tenure and mutual avoidance allow cougars too maintain home ranges in a number of beneficial ways. First they seem to reduce conflict. A large, powerful carnivore like the cougar depends exclusively on its good health to capture prey. Frequent fighting could lead to serious injury and starvation. This is not to say fighting between cats never occurs; as has already been pointed out, in some cougar populations, such as in southern New Mexico, fighting is common and even a major source of mortality.(17) Secondly, maintaining a matrix of adjacent and overlapping home ranges seems to limit cougar population density,(8,21,22) which in turn increases the cats’ chances of finding prey. Finally, because home ranges are frequently hundreds of square miles in size, it would be impossible for a cougar to actively defend the entire area against all intruders.(15) As a result, a more flexible system of coexistence has evolved.

Researchers have learned much of what they know about home ranges through radio telemetry. This involves capturing a wild cougar and attaching a collar containing a small radio transmitter. By plotting the cat’s locations on a topographic map, biologists can learn the size of the area a cougar uses throughout the year, what the density of cats in an area is, and the social structure of the population.(23) What they have learned is that home ranges vary widely in size, depending on local vegetation, prey density, and the time of the year. Male home range size can vary from 25 to 500 square miles, while females usually occupy smaller areas of from 8 to over 400 square miles. Sitton and Wallen documented some of the smallest home ranges in the Big Sur region of coastal California, where the average home ranges were 25 to 35 square miles for males and 18 to 25 square miles for females.(24) A warmer climate and abundant forage probably make it unnecessary for the deer to migrate between winter and summer range and the herds thus concentrate in specific areas. Consequently, the cougar population concentrates around the denser prey population. The presence of good stalking cover is likely a factor as well. Hemker and his colleagues found some of the largest home ranges during the Boulder-Escalante study in southern Utah, where males occupied areas of up to 513 square miles and females up to 426 square miles.(25)

As might be expected, male and female cougars use their home ranges differently.

As might be expected, male and female cougars use their home ranges differently. Besides a place to hunt, males require in area where they can mate with as many females as possible without interference from surrounding males. That is why male home ranges overlap two, three, or more female home ranges and why male home ranges usually do not overlap. Female home ranges are usually smaller and are used to provide sufficient prey and denning sites for rearing kittens, even in years of low prey density.(15)

Life is tough for a female cougar-much tougher than for a male. Seidensticker explains why: “Adult females are subject to more stress and hazards than are males. The female must hunt and kill large, potentially dangerous prey more frequently than males and must do so at regular, predictable intervals if she is to succeed in rearing her kittens, thus increasing the likelihood of accidental death.”(9) On occasion, males have even been known to abandon their home range and move to a new area;(26) older males can also be displaced from their home ranges by prime males.(17) Females show much more attachment to their home ranges and tend to remain in the same area for their entire lives.

The amount of stalking cover and prey numbers in cougar habitat obviously influence home range size. Home range size and the degree of overlap in turn influence the density of a cougar population in a given area.(27) Density estimates of 3 to 7 adult cougars per 100 square miles have been made in southern Alberta(28) and 5 to 8 adult cougars per 100 square miles in the Diablo Mountains of California.(16) Both habitats are characterized by good stalking cover and abundant prey. Lion densities in dryer desert climates seem to be lower. Linda Sweanor and Kenny Logan estimate only 2 adult cougars per 100 square miles in their New Mexico study area, which lies in the Chihuahuan Desert.(29) Densities in southern Utah were even lower, at .5 to .8 adult cougars per 100 square miles, which was 30 percent lower than densities estimated elsewhere.(25) When stalking cover, prey, and water are scarce, cougars expend more energy searching for and stalking prey in larger home ranges. As a result, the cougar population is scattered more thinly across the region. (Fred Lindzey cautions that estimating densities of a solitary and highly mobile predator like the mountain lion is difficult, and that a variety of estimation methods are used by biologists, so one must he careful in making comparisons.(12))

The amount of stalking cover and prey numbers in cougar habitat obviously influence home range size. Home range size and the degree of overlap in turn influence the density of a cougar population in a given area.(27) Density estimates of 3 to 7 adult cougars per 100 square miles have been made in southern Alberta(28) and 5 to 8 adult cougars per 100 square miles in the Diablo Mountains of California.(16) Both habitats are characterized by good stalking cover and abundant prey. Lion densities in dryer desert climates seem to be lower. Linda Sweanor and Kenny Logan estimate only 2 adult cougars per 100 square miles in their New Mexico study area, which lies in the Chihuahuan Desert.(29) Densities in southern Utah were even lower, at .5 to .8 adult cougars per 100 square miles, which was 30 percent lower than densities estimated elsewhere.(25) When stalking cover, prey, and water are scarce, cougars expend more energy searching for and stalking prey in larger home ranges. As a result, the cougar population is scattered more thinly across the region. (Fred Lindzey cautions that estimating densities of a solitary and highly mobile predator like the mountain lion is difficult, and that a variety of estimation methods are used by biologists, so one must he careful in making comparisons.(12))

As a result of the functions of land tenure and mutual avoidance, cougars appear to “saturate” an area at a given density. Research indicates that the density of cougars in a particular area is socially regulated through home range size and overlap and does not increase above a level socially tolerable for cougars. In other words, healthy cougar populations appear to be self-regulating. Harley Shaw explains: “In all studies of lions where relatively good documentation of lion numbers has been made, lion densities have peaked and stabilized at points between ten and twenty square miles per adult resident. Evidence indicates that, if left alone, adult resident lions will probably not populate beyond such densities.”(22)

POPULATION DYNAMICS

Wildlife biologists have long puzzled over the cougar’s solitary life style and how it benefits the animal as a predator. “I find it curious that an animal starting in a litter becomes antisocial in adulthood,” writes Harley Shaw. “The earliest moments of a lion’s life involve touching its siblings. Its growth involves play, interaction, and cooperation during early efforts in hunting. Yet the animal ultimately comes to avoid other adults except at breeding time.”(22)

The cooperative hunting methods of wolves have been extensively studied and their success is well known, as is their gregarious life style. One cannot help but wonder if in comparison the cougar’s solitary life style, especially hunting, puts the cat at a distinct disadvantage. Seidensticker and his fellow researchers don’t think so: “The mountain lion, too, kills large potentially dangerous prey, but unlike the wolf, a pursuit predator, the lion is a stalking predator whose success depends solely on the element of surprise. In the broken land where lions find sufficient cover to stalk and launch successful attacks, the prey usually are scattered and time-consuming to find. Under such conditions, a solitary social structure is apparently the most effective life style.”(9)

While hunting alone may have its advantages, cougars may not be as solitary as once thought. Rick Hopkins points out that adult males are not solitary by choice and probably spend most of their time searching for receptive females.(27) Susan de Treville once monitored four radio collared adult resident males to within 50 yards of each other in the Big Sur region of California.(30) Andrew Kitchener writes: “…far from having a chaotic, random system of home ranges driven by the need for [solitary] cats to avoid each other at all costs, most wild cats maintain a predictable system of land tenure, which promotes social stability and maximizes the reproductive success of both males and females… far from being strangers, neighboring cats probably know each other very well from their own distinctive smells.”(15)

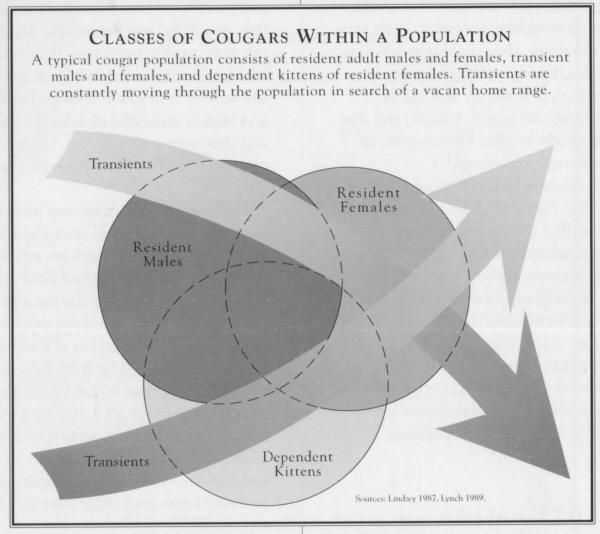

Solitary or not, cougars that inhabit a common geographic area are referred to as a population,(1) and within a population not all cougars are created equal. This feline social hierarchy consists of three classes of animals: resident adult males and females, transient males and females, and dependent offspring of resident females. Resident adults maintain established home ranges and do most of the breeding in a population. Transients constantly move through the home ranges of residents in search of a vacant home range of their own; while female transients tend to delay breeding until they find and occupy a home range, this may not be true of males. Dependent offspring include kittens and juveniles that still rely on their mother to hunt for them.(23)

Determining whether a cougar is an adult, transient, or kitten is more complex than it sounds; finding a reliable way to determine age is something which has long eluded biologists. Age is usually established using a combination of tooth wear, body weight, color spotting, and behavior. Kittens are newborn to 16 months old and are still with their mother in her home range; they may still have spots which fade by the third of fourth month. Transients are 17 to 23 months old and have left their mother’s home range but have not yet settled in a home range of their own; spotting may still be present on the insides of the front legs. Resident adults are mature cats, at least 24 months old, and occupy an established home range; spotting is absent or very faint, and females may show evidence of nursing.(26)

Harley Shaw uses a slightly different system of classifying lions. Resident lions are adult males and females that use established home ranges and are reproductively active. Immature lions are defined as offspring of resident adults that are still traveling with, or close to, the mother. Transient lions are young, newly independent adults searching for a home range.(31)

reproductively active. Immature lions are defined as offspring of resident adults that are still traveling with, or close to, the mother. Transient lions are young, newly independent adults searching for a home range.(31)

Researchers Kenny Logan and Linda Sweanor prefer the terms emigrant and disperser to transient. These refer to lions that have emigrated or dispersed from their birth area but have not set up a home range. This dispersal out of a previously occupied area is called emigration, while movement into a new area is called immigration.(1) Emigrants become immigrants when they enter a new population.(17) (While it is good science for researchers to refine their techniques and terms, the lack of consistency also makes it difficult for scientists to compare information. It also frustrates writers attempting to explain mountain lions.)

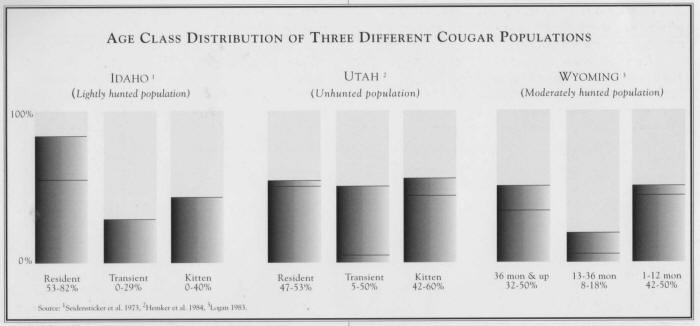

Because no reliable method yet exists for accurately aging cougars, determining how many resident adults, transients, and kittens are present in a cougar population at any given time is equally difficult. This is further complicated by the fact that young transient cats are constantly on the move.(12) These factors, if not accounted for, can distort population estimates made by wildlife biologists.

Resident females generally outnumber resident males in a population.(25,32,33) This may be because females require smaller home ranges that frequently overlap those of other female cougars. Females also seem generally more tolerant of adjacent females and, as a result, more females might concentrate in a smaller area. Resident males, on the other hand, require larger home ranges that rarely overlap, and they tend to be intolerant of other males and are more widely scattered than resident females.

Young transient cougars usually leave their mother’s home range (disperse) sometime during their second year. The newly independent cats occasionally linger in the birth area, while others leave immediately. They may wander for more than a before establishing their own home range.(22) If sufficient space is available, however some females will remain in their birth areas; one young female in Nevada stayed in the mountain range of her birth, bred at 24 months, and established a home range adjacent to her mother’s. Female transients have even been known to take over their mother’s home range after her death.(18)

Males tend to wander farther than females,(26) although how far either gender travels seems to vary. Transient males in the Diablo Mountains of California traveled up to 35 miles from their areas of birth.(16) In one Nevada population, males covered an average of 31 miles, while females averaged 18 miles.(26) One young cougar marked in the Bighorn Mountains of Wyoming appeared in northern Colorado, 300 miles from the original location.(34)

Transient males and females seldom remain in one location longer than six months.

Transient males and females seldom remain in one location longer than six months. How the cats “test” a population for vacant home ranges is poorly understood. It is generally thought that a transient either finds a vacant home range or displaces an older resident. If a vacant home range is found, the young male or female will settle down to the business of establishing its place in the population. If the population density is so high that no vacant home areas exist, the transient moves on.

Kenny Logan believes male transients enter a new population and for a period of time, make kills, avoid other lions, and avoid scrapings. If they think they can establish a home range they begin to scrape. Meanwhile, the resident male, closely monitoring its home range, is busy investigating the newcomer’s scrapes and kills. If the resident and newcomer encounter each other they may fight. As a result, the resident may kill the newcomer, the newcomer may kill the resident, or the newcomer may drive off or displace the resident.(17)

The role of transients in populations is important because they are the primary source of replacements for resident cougars who die as a result of hunting, old age, or accidents. Transients also ensure genetic mixing between populations,(12) and appear to be a major factor in the recovery of hunted populations. Cougar populations in isolated mountain ranges, such as those common to the Great Basin, are particularly vulnerable because immigration of transients is low.(35)

For example, aggressive predator control efforts wiped out all cougars in and around Yellowstone National Park by the 1920s, and – except for a few transients passing through – no cougars lived there for almost 50 years. But transients seem to be slowly recolonizing the 2.2 million-acre park; research biologist Kerry Murphy directs a field study of cougars in the region and estimates 14 to 17 resident mountain lions are now present. Radio collars have been attached to 9 females and 7 males, and the population produced 21 kittens in 1991. The region has abundant deer and elk, and the cougar population is increasing.(36)

As mentioned earlier, the availability of good hunting sites and prey numbers limit the number of cougars in an area. But birth, death, emigration, and immigration are all factors that greatly influence cougar population maintenance and growth. In absence of hunting by humans, the cougar population will remain relatively constant.(12) Rick Hopkins found that the unhunted cougar population in the Diablo Mountains of California was relatively stable with a low turnover of residents.(16)

COUGARS ON THE MOVE

There is nothing more distinctive about cats than the way they move, and mountain lions are no different. The big cats are the epitome of graceful, lithe motion. Stealthy shadows that do not move so much as flow across the landscape.

Consider the effect of broken terrain on prey, explains Kenny Logan. “Mountain lions are ballerinas at getting across broken terrain-steep slopes, boulders, outcroppings, and undercut ledges.” Mule deer and elk are not as good at negotiating such rugged landscapes.(17) Here the cougar uses both cover and superior agility to its advantage, and employs yet another weapon in its predatory arsenal-it hunts under the cover of darkness.

Cougars are not strictly nocturnal, as many once thought.

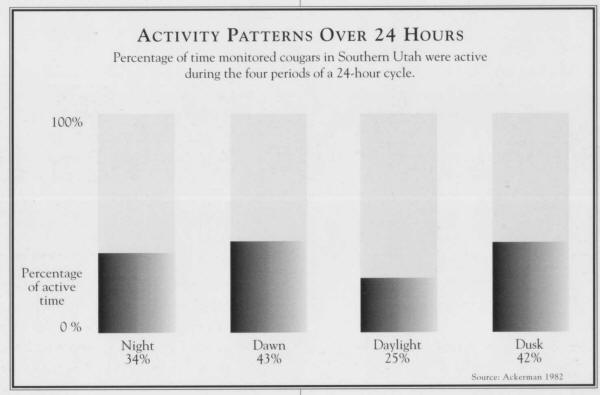

Cougars are not strictly nocturnal, as many once thought. Rather, they tend to be active at the same time as their prey, and deer tend to be active at dawn, dusk, and at night. Animals that are active during the twilight of dawn and dusk are said to be crepuscular. The big cat’s excellent night vision makes it well suited for stalking during these low light periods. Florida panthers appear to be more active at sunrise and sunset,(37) and Paul Beier reports that in southern California mountain lions are active throughout the night.(39) During the winter in Idaho, radio-collared cougars were found to be more active at night (40 percent of the time they were located) than during daylight hours (14 percent of the time they were located). Daytime activity increased during the summer with an increased abundance of ground squirrels.(9) Bruce Ackerman studied cougar activity patterns in southern Utah and found the cats most active at sunrise and sunset, but less so during the winter. He also found that single adults were more active than females with young, but that the females became more active as their kittens grew.(3)